It has been nearly two centuries since Charles

Grandison Finney was licensed to preach. Christianity

Today recognizes him as “the most effective evangelist America had ever

seen,” influencing through his evangelism, directly or indirectly, an estimated

half a million people to make decisions to follow Christ. His innovative

crusade tactics and unconventional approach to theology, while stirring controversy at the time

(which continues in theological debates today), were central to the second

phase of America’s Second Great Awakening. Finney was licensed to preach on

this date, December 30, in 1823. And oh,

how our nation could use another Finney today.

Saturday, December 30, 2017

Tuesday, September 26, 2017

A Reason to Celebrate! 500 Years Since the Reformation Began

In less than a

month, Protestant churches will have great reason to celebrate their heritage.

Oct. 31 will be the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s posting of

his 95 theses on the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. The event

precipitated the Reformation and the recapturing of great Christian truths and

practices that had been mired in murky tradition and ecclesiastical corruption

during the middle ages.

Under Luther’s impetus, the Evangelical Church was reborn, restoring the individual access to the great tenets of genuine religion: the scriptures available to all people in their own languages, salvation by grace through faith in Jesus Christ alone, with all glory going to God alone, the priesthood of all believers.

I pray that all of

our pastors recognize the importance of this event and recognize it from their

pulpits.

Williston Walker,

in his volume The Reformation in the

set Ten Epochs of Church History by

John Fulton, closes the book with an assessment which follows (in part). If

you’re not convinced yet, perhaps the words of this superb Church historian

will help (pp. 461ff.):

“The Reformation age is the most striking

period in religious history since the

days of the early Church. The threads of

all modern religious life in western Christendom run back into it. …

“[Its tenets] touched society and the common man in the

relationships of every-day life, of personal piety, of government and of social

welfare. It was not an age of … abstruse theology. It was preeminently an

epoch of deeds.

…

“[As] mighty as were the giants of the

Reformation age, the principles that they championed were yet mightier. The

central impulse of the Reformation was a revival of religion. … That

desire, in a new and revolutionary faith that strove to burst the shackles of

externalism which the middle ages had imposed and to bring the human soul into

direct contact with God, was the starting-point of Luther's work. The

Reformation vitalized the religious life of Europe.

“To the Protestant, the profoundest

obligations were to use his divinely-given faculties to ascertain for himself

what is the truth of God as contained — so the Reformation age would say — in

His infallible and absolutely authoritative Word; and to enter through faith

into vital, immediate and personal relations with his Savior.

…

“No wise Protestant will lightly value the

birthright of freedom which the Reformation won for him. Nor can he regard a

movement which has stimulated independence of religious thought, has

promoted investigation, has emphasized

individual responsibility, and has made social, political and intellectual life

freer in a thousand ways as other than an unmeasured blessing.

…

“Christendom has reason to rejoice to this

day that the transition from the mediaeval to the modern world was accompanied

by a profound, searching and transforming revival of religion.”

May we recapture these great Reformation

truths!

Saturday, July 1, 2017

It's the Centennial of the U.S. Entry into World War 1

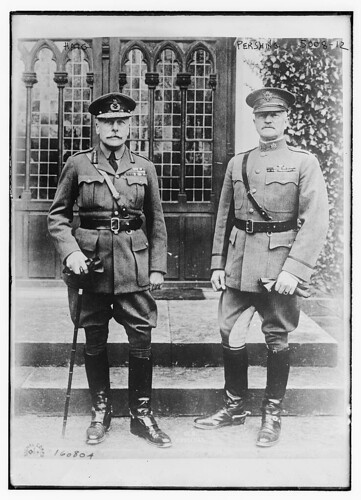

Douglas Haig and John Joseph Pershing

An interesting near contemporary account from:

BOYS' BOOK OF FAMOUS SOLDIERS

BY J. WALKER McSPADDEN

THE WORLD PUBLISHING CO.

CLEVELAND, OHIO —— NEW YORK, N. Y.

[Public Domain]

HAIG

THE MAN WHO LED "THE CONTEMPTIBLES"

"There goes young Haig. He says he intends to be a soldier."

The speaker was a young student at Oxford University, as he jerked his thumb in the direction of a slight but well-set-up fellow, a classmate, who went cantering past.

The chance remark, made more than once during the college days of Field Marshal Haig, struck the keynote of his career. From early boyhood Douglas Haig was going to be a soldier; and he stuck to his guns in a quiet, systematic way until he won out.

The story of Haig's life until the time of the Great War, was the opposite of spectacular, and even in it, his personal prowess was kept studiously in the background. With him it has always been: "My men did thus and so." Yet in his quiet way he has always made his presence felt with telling effect. He has been the man behind the man behind the gun.

By birth Haig was a "Fifer," which sounds military without being so. He was a native of Cameronbridge, County of Fife, and came of the strictest Presbyterian Scotch. If he had lived a few centuries back he would have been a Covenanter—the kind that carried a Bible in one hand and a gun in the other. He was born, June 19, 1861, the youngest son of John Haig, a local Justice of the Peace. His mother was a Veitch of Midlothian.

The family, while not wealthy, was comfortably situated. The Haig children grew up as countrywise rather than townbred, having many a romp over the rolling country leading to the Highlands. But more than once on such a jaunt would come the inquiry: "Where's Douglas?" (We doubt whether they ever shortened it to "Doug," as they would have done in America.) And back would come the answer: "Oh, he stayed by the house, the morn. He got a new book frae the library, ye ken."

Douglas was, indeed, bookish and was inclined to favor the inglenook rather than the heather. As he grew older he discovered a strong liking for books on theology. It was the old Presbyterian streak cropping out.

The last thing one would expect from such a boy, was to become a soldier. A divinity student, yes,—perhaps a college professor—but a soldier, never! Yet it was to soldiering that this quiet boy turned.

The one thing which linked him up with the field was horsemanship. He was always a devotee of riding, and soon learned to ride well, with a natural ease and grace.

He received a general education at Clifton, then entered Brasenose College, Oxford, at the age of twenty. He was never a "hail-fellow-well-met" sort of person. Reserve was his hallmark. But the longer he stayed in college, the more of an outdoorsman he became. Every afternoon would find him mounted on his big gray horse for a gallop across the moors, or perhaps an exciting canter behind the hounds on the scent of a fox. It was then that his habitual reserve would melt away, and he would wave his hat and cheer like a high-school boy.

The record of his classes is in no sense remarkable. He turned in neat and precise papers, without making shining marks in any particular study. Literature and science were his best subjects.

"Well, son, how goes it now?" his father would ask. "Ready to make a lawyer out of yourself?"

Douglas would shake his head. He could never share his father's enthusiasm for the law. "I guess not, father," he would reply quietly. "Somehow, I am not built that way. I want a try at soldier life."

So his father let him follow his bent, and procured for him a position in the Seventh Regiment of Hussars. His career as a soldier was threatened at the outset by the refusal of the medical board to admit him to the Staff College on the ground that he was color-blind; but this decision was over-ruled by the Duke of Cambridge, then commander-in-chief, who nominated him personally. This was in 1885. England was then as nearly at peace as she ever became, and it seemed that young Haig was destined to become a feather-bed soldier.

But it was not for long. They presently began to stir up trouble down in Egypt, and England found, as on many previous occasions, that she didn't have half enough regulars for the job in hand. The revolt of the Mahdi had occurred, Khartoum had fallen, and the brave Gordon had lost his life.

A relief expedition into the Soudan was organized under the command of a tall, stern soldier named Kitchener, who began his first preparations to march into the interior about the time that Haig was putting on his first Hussar uniform.

The campaign in Egypt dragged, despite the zeal of the leader. In disgust, Kitchener returned to England to demand more men. The request was at last granted, and by December, 1888, he was in command of a force of over 4,000 troops, of which number 750 were British regulars! Those were indeed the days of the "Little Contemptibles," but right manfully they measured up to their tasks. And in the British force was the Seventh Hussars, including Haig. He was about to achieve his life's ambition, at last—to see real service as a British soldier.

Haig was then a well-knit young man of twenty-seven. His outdoor exercise had browned and hardened him, until he looked thoroughly fit for the exacting job ahead. He was slightly under medium size, but tough and wiry to the last degree. His shoulders were broad, his head well set, and the bulging calves of his legs showed the born cavalryman. He had fair, almost sandy hair, a close-cropped mustache, and steel-blue eyes which met honestly and unflinchingly the gaze of any with whom he talked. He looked then, as in later years, "every inch a soldier," and speedily won the confidence of his superiors.

The silent Kitchener, who was a keen judge of men, soon took a fancy to this quiet young lieutenant. A friendship sprang up between them, that was destined to bear far-reaching fruit. The two men were both reserved in demeanor, but in a different sort of way. Kitchener was taciturn and often inclined to growl. Haig was a man of few words and no intimates, but greeted all with a pleasant smile. To this young Scotsman Kitchener unbent more than was his wont, and was actually seen shaking hands with him, at parting, on a later occasion; which all goes to show that even commanding officers can be human.

On the march into the Soudan, Kitchener was in command of the Egyptian Cavalry also. The Khedive was exceedingly anxious that the rebellion be crushed speedily, and had made Kitchener the "sirdar." One of the first actions in this campaign was the Battle of Gemaizeh. Three brigades were sent to storm the forts held by the dervishes, and a heavy and sustained fire from three sides soon drove the enemy out in disorder. Some 500 dervishes were slain, and the remainder numbering several thousand fled across the desert toward Handub—closely pursued by the British Hussars and the Egyptian cavalry.

This was only the first of many such actions. Further and further south the rebels were driven. Kitchener pushed a light railroad across the desert as he advanced, so that he would not suffer from the same mistake which had ended Gordon—getting cut off from his base of supplies.

And in the thick of it was Haig—learning the actual trade of war in these frequent brushes on the desert—riding hard by day, sleeping the sleep of exhaustion at night. On more than one occasion the Chief sent him on a special quest with important messages, and always Haig got through. He seemed to bear a charmed life. "Lucky Haig," the men began to call him, and the title stuck.

Entering the desert as a Lieutenant, he was promoted to Captain, then brevetted a Major. He was mentioned in the despatches for bravery, and won a medal from the Khedive.

All this was not done in a few short months. The Egyptian campaign stretched into years, and at times must have seemed fearfully monotonous to these soldiers so far removed from home comforts. Here is the way one writer describes the Soudan:

"The scenery, it must be owned, was monotonous, and yet not without haunting beauty. Mile on mile, hour on hour, we glided through sheer desert. Yellow sand to right and left—now stretching away endlessly, now a valley between small broken hills. Sometimes the hills sloped away from us, then they closed in again. Now they were diaphanous blue on the horizon, now soft purple as we ran under their flanks. But always they were steeped through and through with sun—hazy, immobile, silent."

One of the culminating battles of the campaign was that of Atbara, where the backbone of the dervish rebellion was broken. It is estimated that here 8,000 dervishes were killed, 2,000 wounded, and 2,000 made prisoners. The battle began with a bombardment by the field guns. Then came the British cavalry at a gallop—the Camerons in front, and columns of Warwicks, Seaforths, and Lincolns behind. Bugles, bagpipes, and the instruments of the native regiments made strange music as the army pressed forward intent on reaching the river bank.

The native stockades were reinforced with thorn bushes, but these were torn away by the men, with their bare hands, in their eagerness to advance. Haig's regiment was one of the first to penetrate, but once past the stockade they encountered many of the defenders who put up a fierce fight. Several British officers lost their lives, and it was due to Haig's agility and presence of mind that he was not at the least severely wounded. Two dervishes attacked him at once from opposite sides. One aimed a slashing blow at his head with a scimitar. Haig quickly ducked and the scimitar went crashing against the weapon of the other dervish. Haig's luck again!

Others were not so fortunate. "Never mind me, lads, go on," said Major Urquhart with his dying breath. "Go on, my company, and give it to them," gasped Captain Findlay as he fell. At the head of the attacking party strode Piper Stewart, playing "The March of the Cameron Men," until five bullets laid him low. Truly the spirit of the fiery old Covenanters was there!

The final battle of the Soudanese campaign, Khartoum, put the finishing touches to the rebellion, and gave to Kitchener the title "K. of K."—Kitchener of Khartoum. This battle was noteworthy in employing the cavalry in an open charge across the plains against the dervish infantry. It was just such a charge as a skilled horseman such as Haig would keenly enjoy, despite the danger. Winston Churchill, the British Minister, thus describes it:

"The heads of the squadrons wheeled slowly to the left, and the Lancers, breaking into a trot, began to cross the dervish front in column of troops. Thereupon and with one accord the blue-clad men dropped on their knees, and there burst out a loud, crackling fire of musketry. It was hardly possible to miss such a target at such a range. Horses and men fell at once. The only course was plain and welcome to all. The Colonel, nearer than his regiment, already saw what lay behind the skirmishers. He ordered 'Right wheel into line' to be sounded. The trumpet jerked out a shrill note, heard faintly above the trampling of the horses and the noise of the rifles. On the instant the troops swung round and locked up into a long, galloping line.

"Two hundred and fifty yards away, the dark blue men were firing madly in a thin film of light-blue smoke. Their bullets struck the hard gravel into the air, and the troopers, to shield their faces from the stinging dust, bowed their helmets forward, like the Cuirassiers at Waterloo. The pace was fast and the distance short. Yet before it was half covered the whole aspect of the affair changed. A deep crease in the ground—a dry watercourse, a khor—appeared where all had seemed smooth, level plain; and from it there sprang, with the suddenness of a pantomime effect and a high-pitched yell, a dense white mass of men nearly as long as our front and about twelve deep. A score of horsemen and a dozen bright flags rose as if by magic from the earth. The Lancers acknowledged the apparition only by an increase of pace."

In such a mêlée as then followed, that trooper was lucky indeed who escaped without a scratch.

As a result of his bravery at Atbara and Khartoum, Haig's name was mentioned in the official despatches. He returned to England wearing the Khedive's medal and the honorary title of Major.

It is probable, however, that little more would have been heard of him, had not the South African War broken out, soon after. It is the lot of military men to vegetate in days of peace. They live upon action. Haig was no exception to this rule. He welcomed new fields. He went to South Africa as aide and right-hand man to Sir John French—the general whom he was to succeed in later years on the battlefields of France.

In this war, Haig is not credited with many personal exploits. His was essentially a thinking part. Yet he served as chief of staff in a series of minor but important operations about Colesburg, which prepared the way for Roberts's advance. As usual Haig pinned his faith upon the cavalry. All his life he had made a close study of this arm of the service, and was of opinion that it was not utilized in modern warfare nearly so much as it should be. He was a warm admirer of the American officer, J. E. B. Stuart, the Confederate General whose dashing tactics turned the scale in so many encounters.

Now he tried the same strategy in the operations around Colesburg—and paved the way for later victory.

Haig somewhat resembled another Southern leader, Stonewall Jackson, in his piety. It was not ostentatious, but simply part and parcel of the man, due to his Presbyterian training. Haig did not swear or gamble or dance all night. He was more apt to be found in his tent, when off duty, either reading or writing.

They tell of him that, one day at the officers' mess, after a particularly lively brush with the Boers, the quartermaster asked him if he had lost anything.

"Yes," replied Haig solemnly, "my Bible!"

Not once did his countenance relax its gravity, as he met the grinning faces across the table.

But despite their chaffing, there was not a man there who did not respect the courage of his convictions, no less than the bravery of the man himself. Almost daily he risked his life in these cavalry operations—until the "Haig luck" became a watchword.

The end of the South African War found Haig promoted to acting Adjutant

General of the Cavalry, and soon after his return home he was made

Lieutenant Colonel, in command of the Seventeenth Lancers. This was in

1901.

About this time he paid a visit to Germany, then at peace and professing a warm affection for England. One result of this visit was a letter which showed him possessed with wonderful powers of analysis and foresight. He practically predicted the war that was to come. He summed up his observations in a long letter to a friend which, in the light of events of the War, is little short of uncanny. It gave the German plan with a mastery of detail, shrewd prophecy, and earnest warning. The future commander-in-chief of the British armies in France was convinced of the certainty of the conflict and besought the authorities to make better preparation—but his warnings fell upon deaf ears.

It required thirteen years to demonstrate the truth of Haig's predictions, and then the blow fell. The Kaiser viewed his strong hosts and boasted that he would soon wipe out England's "contemptible little army." He very nearly did so, and would certainly have succeeded, had it not been for the fighting spirit of such men as Haig.

During the intervening years since the South African campaign he had risen by fairly rapid stages to Inspector-General of the Cavalry in India—a situation which he handled with great skill for three years—then Major General, and Lieutenant General.

At the outbreak of the World War, he was hurriedly sent to France, under the command of Sir John French, his old leader in Africa. French was generosity itself in his praise of Haig in these early days of disaster.

In the retreat from Mons it was "the skilful manner in which Sir Douglas Haig extricated his corps from an exceptionally difficult position in the darkness of the night," that won his laudation. At the Aisne, on September 14, 1914, "the action of the First Corps on this day, under the direction and command of Sir Douglas Haig, was of so skilful, bold, and decisive a character, that he gained positions which alone have enabled me to maintain my position for more than three weeks of very severe fighting on the north bank of the river."

In the first battle of Ypres, the chief honors of victory were again awarded to him:

"Throughout this trying period, Sir Douglas Haig, aided by his divisional commanders and his brigade commanders, held the line with marvelous tenacity and undaunted courage."

Again and again, the generous French pays tribute to his friend, which while deserved reflects no less honor upon the speaker. He was big enough to share honor.

It is not strange, therefore, when French was superseded, for strategic reasons, that Haig should have been given the chief command. The appointment, however, left most of the world frankly amazed. Haig had come forward so quietly that few save those in official circles knew anything about him. It was nevertheless but a matter of weeks, possibly days, before a quiet confidence born of the man himself was manifest everywhere.

One war correspondent who visited headquarters in the midst of the

War's turmoil, thus describes his visit:

"The environment of the Commander-in-chief is strongly suggestive of his conduct of the war. Before war became a thing of precise science, the headquarters of an army head seethed with all the picturesque details so common to pictures of martial life. Couriers mounted on foam-flecked horses dashed to and fro. The air was vibrant with action; the fate of battle showed on the face of the humblest orderly. But today 'G. H. Q.'—as headquarters are familiarly known—are totally different. Although army units have risen from thousands to millions of men, and fields of operations stretch from sea to sea, and more ammunition is expended in a single engagement than was employed in entire wars of other days, absolute serenity prevails. It is only when your imagination conjures up the picture of flame and fury that lies beyond the horizon line that you get a thrill.

"An occasional motorcar driven by a soldier-chauffeur chugs up the gravel road to the chateau and from it emerge earnest-faced officers whose visits are usually brief. Neither time nor words are wasted when myriad lives hang in the balance and an empire is at stake. Inside and out there is an atmosphere of quiet confidence, born of unobtrusive efficiency."

The same writer on meeting Haig says: "I found myself in a presence that, even without the slightest clue to its profession, would have unconsciously impressed itself as military. Dignity, distinction, and a gracious reserve mingle in his bearing. I have rarely seen a masculine face so handsome and yet so strong. His hair and mustache are fair, and his clear, almost steely-blue eyes search you, but not unkindly. His chest is broad and deep, yet scarcely broad enough for the rows of service and order ribbons that plant a mass of color against the background of khaki. . . .

"Into every detail of daily life at General Headquarters the Commander's character is impressed. After lunch, for example, he spends an hour alone, and in this period of meditation the whole fateful panorama of the war passes before him. When it is over the wires splutter and the fierce life of the coming night—the Army does not begin to fight until most people go to sleep—is ordained.

"This finished, the brief period of respite begins. Rain or shine, his favorite horse is brought up to the door, and he goes for a ride, usually accompanied by one or two young staff-officers. I have seen Sir Douglas Haig galloping along those smooth French roads, head up, eyes ahead—a memorable figure of grace and motion. He rides like those latter-day centaurs—the Australian ranger and the American cowboy. He seems part of his horse."

Such was the man who did his full share in turning the German tide. Throughout the four long years of war, he faced the enemy with a calm courage which if it ever wavered gave no outward sign. And that is one reason why the Little Contemptibles grew and grew until they became a mighty barrier stretching across the pathway of the invader from sea to sea, and saying with their Allies:

"You shall not pass!"

IMPORTANT DATES IN HAIG'S LIFE

1861. June 19. Douglas Haig born. 1880. Entered Brasenose College, Oxford. 1885. Joined 7th Hussars, British army. 1898. Served in Soudan, mentioned in despatches, and brevetted major. 1899. Served in South Africa. D. A. A. G. for cavalry; then staff officer to General French. 1901. Lieutenant-colonel commanding 17th Lancers. 1903. Inspector-general, cavalry, India. 1904. Major-general. 1910. Lieutenant-general. 1914. General, commanding First Army in France. 1915. Commander-in-chief of British forces. 1917. Field marshal. 1919. Created an earl. 1928. January 30. Died in England.

PERSHING

THE LEADER OF AMERICA'S BIGGEST ARMY

It was a historic moment, on that June day, in the third year of the World War. On the landing stage at the French harbor of Boulogne was drawn up a company of French soldiers, who looked eagerly at the approaching steamer. They were not dress parade soldiers nor smart cadets—only battle-scarred veterans home from the trenches, with the tired look of war in their eyes. For three years they had been hoping and praying that the Americans would come—and here they were at last!

As the steamer slowly approached the dock, a small group of officers might be discerned, looking as eagerly landward as the men on shore had sought them out. In the center of this group stood a man in the uniform of a General in the United States Army. There was, however, little to distinguish his dress from that of his staff, except the marks of rank on his collar, and the service ribbons across his breast. To those who could read the insignia, they spelled many days of arduous duty in places far removed. America was sending a seasoned soldier, one tried out as by fire.

The man's face was seamed from exposure to the suns of the tropics and the sands of the desert. But his dark eyes glowed with the untamable fire of youth. He was full six feet in height, straight, broad-shouldered, and muscular. The well-formed legs betrayed the old-time calvalryman. The alert poise of the man showed a nature constantly on guard against surprise—the typical soldier in action.

Such was General Pershing when he set foot on foreign shore at the head of an American army—the first time in history that our soldiers had ever served on European soil. America was at last repaying to France her debt of gratitude, for aid received nearly a century and a half earlier. And it was an Alsatian by descent who could now say:

"Lafayette, we come!"

Who was this man who had been selected for so important a task? The eyes of the whole world were upon him, when he reached France. His was a task of tremendous difficulties, and a single slip on his part would have brought shame upon his country, no less than upon himself. That he was to succeed, and to win the official thanks of Congress are now matters of history. The story of his wonderful campaign against the best that Germany could send against him is also an oft-told story. But the rise of the man himself to such commanding position is a tale not so familiar, yet none the less interesting.

The great-grandfather of General Pershing was an emigrant from Alsace—fleeing as a boy from the military service of the Teutons. He worked his way across to Baltimore, and not long thereafter volunteered to fight in the American Revolution. His was the spirit of freedom. He fled to escape a service that was hateful, because it represented tyranny; but was glad to serve in the cause of liberty.

The original family name was Pfirsching, but was soon shortened to its present form. The Pershings got land grants in Pennsylvania, and began to prosper. As the clan multiplied the sons and grandsons began to scatter. They had the pioneer spirit of their ancestors.

At length, John F. Pershing, a grandson of Daniel, the first immigrant, went to the Middle West, to work on building railroads. These were the days, just before the Civil War, when railroads were being thrown forward everywhere. Young Pershing had early caught the fever, and had worked with construction gangs in Kentucky and Tennessee. Now as the railroads pushed still further West, he went with them as section foreman—after first persuading an attractive Nashville girl, Ann Thompson, to go with him as his wife.

Their honeymoon was spent among the hardships of a construction camp in

Missouri; and here at Laclede, in a very primitive house, John Joseph

Pershing was born, September 13, 1860.

The boy inherited a sturdy frame and a love of freedom from both sides of the family. His mother had come of a race quite as good as that of his father. They were honest, law-abiding, God-fearing people, who saw to it that John and the other eight children who followed were reared soberly and strictly. The Bible lay on the center table and the willow switch hung conveniently behind the door.

After the line of railroad was completed upon which the father had worked, he came to Laclede and invested his savings in a small general store. It proved a profitable venture. It was the only one in town, and Pershing's reputation for square-dealing brought him many customers. A neighbor pays him this tribute:

"John F. Pershing was a man of commanding presence. He was a great family man and loved his family devotedly. He was not lax, and ruled his family well.

"The Pershing family were zealous church people. John F. Pershing was the Sunday School superintendent of the Methodist Church all the years he lived here. Every Sunday you could see him making his way to church with John on one side and Jim on the other, Mrs. Pershing and the girls following along."

John F. Pershing was a strong Union man, and although local feeling ran high between the North and the South, he retained the esteem of his neighbors. He had one or two close calls from the "bushwhackers," as roving rangers were called, but his family escaped harm.

At times during the War, he was entrusted with funds by various other families, and acted as a sort of local bank. After the War he was postmaster.

The close of the War found the younger John a stocky boy of five. He began to attend the village school and take an active part in the boyish sports of a small town. There was always plenty to do, whether of work or play. One of his boyhood chums writes:

"John Pershing was a clean, straight, well-behaved young fellow. He never was permitted to loaf around on the streets. Nobody jumped on him, and he didn't jump on anybody. He attended strictly to his own business. He had his lessons when he went to class. He was not a big talker. He said a lot in a few words, and didn't try to cut any swell. He was a hard student. He was not brilliant, but firm, solid, and would hang on to the very last. We used to study our lessons together evenings. About nine-thirty or ten o'clock, I'd say:

"'John, how are you coming?'

"'Pretty stubborn.'

"'Better go to bed, hadn't we?'

"'No, Charley, I'm going to work this out.'"

Another schoolmate gives us a more human picture:

"As a boy, Pershing was not unlike thousands of other boys of his age, enjoying the same pleasures and games as his other boyhood companions. He knew the best places to shoot squirrels or quail, and knew where to find the hazel or hickory nuts. He knew, too, where the coolest and deepest swimming pools in the Locust, Muddy, or Turkey creeks were. Many a time we went swimming together in Pratt's Pond."

About this time Pershing's father added to his other ventures the purchase of a farm near Laclede, and the family moved out there. Then there was indeed plenty of work to do. The chores often began before sun-up, and lasted till after dark; and the children were lucky to find time for schooling during the late Fall and Winter months. John, however, kept doggedly at it, and managed to get a fair, common-school education.

When he was barely in his 'teens, his first set task was given him—to teach in a negro school. This school had been established after the War ended, but the teacher had gone, and no one else seemed available for the job. John was sober and studious, and besides was so well grown for his age that they banked on his ability to "lick" any negro boy that got obstreperous.

He succeeded sufficiently in this venture, to cause him to take up teaching regularly, in white schools, with a view to paying for his education. He wanted to study law, and his parents encouraged the idea. His work in these country schools was invaluable to him in teaching him how to govern others. A former pupil of his writes:

"Though he never sought a quarrel, young Pershing was known as 'a game fighter,' who never acknowledged defeat. One day, at Prairie Mound, at the noon hour a big farmer with red sideburns rode up to the schoolhouse with a revolver in his hand. Pershing had whipped one of the farmer's children, and the enraged parent intended to give the young schoolmaster a flogging.

"I remember how he rode up cursing before all the children in the schoolyard, and how another boy and I ran down a gully because we were afraid. We peeked over the edge, though, and heard Pershing tell the farmer to put up his gun, get down off his horse, and fight like a man.

"The farmer got down and John stripped off his coat. He was only a boy of seventeen or eighteen and slender, but he thrashed the old farmer soundly. And I have hated red sideburns ever since."

After several terms of country school teaching, young Pershing saved up enough money to enter the State Normal School, at Kirksville, Mo. One of his sisters went with him. He remained there for two terms, doing his usual good steady work, but was still dissatisfied. He wanted to get a better education.

About this time he happened to notice an announcement of a competitive examination in his district for an entrance to West Point. The soldiering side did not appeal to him, but the school side did.

"I wouldn't stay in the army," he remarked to a friend. "There won't be a gun fired in the world for a hundred years, I guess. If there isn't, I'll study law, but I want an education, and now I see how I can get it."

His mother was by no means "sold" on the idea of his becoming a soldier either, and it was only when he assured her that there wouldn't be a gun fired in a hundred years, that she finally consented. If she could have looked ahead to his future career, and final part in the greatest war the world has ever known—one wonders what her emotions would have been!

Pershing passed his entrance examination by a narrow margin, and then entered a training school at Highland Falls, N. Y., for tutoring in certain deficient branches. At last in June, 1882, when he was just rounding his twenty-second year, he became a freshman in the great Academy on the Hudson.

The young plebe from the West speedily fell in love with the institution and all that it represented. He found the soldier life awakening in him, along with his desire for a good education. Four happy years were spent there—and while he didn't shine, being number thirty in a class of seventy-seven, his all-around qualities made him many friends among both faculty and students. He was made ranking cadet captain in his senior year, and chosen class president.

Twenty-five years later, writing from clear around the world, at Manila, to his class, at a reunion, he gives a long, breezy account of his experience there, from which we have space to quote only a few sentences:

"This brings up a period of West Point life whose vivid impressions will be the last to fade. Marching into camp, piling bedding, policing company streets for logs or wood carelessly dropped by upper classmen, pillow fights at tattoo with Marcus Miller, sabre drawn, marching up and down superintending the plebe class, policing up feathers from the general parade; light artillery drills, double-timing around old Fort Clinton at morning squad drill; Wiley Bean and the sad fate of his seersucker coat; midnight dragging, and the whole summer full of events can only be mentioned in passing.

"No one can ever forget his first guard tour with all its preparation and perspiration. I got along all right during the day, but at night on the color line my troubles began. Of course, I was scared beyond the point of properly applying any of my orders. A few minutes after taps, ghosts of all sorts began to appear from all directions. I selected a particularly bold one and challenged according to orders: 'Halt, who comes there?' At that the ghost stood still in its tracks. I then said: 'Halt, who stands there?' Whereupon the ghost, who was carrying a chair, sat down. When I promptly said: 'Halt, who sits there?' . . .

"The career of '86 at West Point was in many respects remarkable. There were no cliques, no dissensions, and personal prejudices or selfishness, if any existed, never came to the surface. From the very day we entered, the class as a unit has always stood for the very best traditions of West Point."

While Pershing was still in West Point, the Indian chief Geronimo was making trouble in the Southwest. For several years he led a band of outlaw braves, who terrorized the Southern border. General Crook was sent in pursuit of him, and afterwards General Miles took up the chase. Finally in August, 1886, the chief and his followers were rounded up.

Pershing graduated in the spring of this year, with the usual rank given to graduates, second lieutenant, and was immediately assigned to duty under Miles. He had an inconspicuous part in the capture. But the next year in the special maneuvers he was personally complimented by the General for "marching his troops with a pack train of 140 mules in 46 hours and bringing in every animal in good condition." Doubtless his early experience with the Missouri brand of mule aided him.

Thereafter, for the next five years, Pershing's life was that of a plainsman. He was successively at Fort Bayard, Fort Stanton, and Fort Wingate, all in New Mexico, in the center of troubled country. In 1890 he was shifted north to take the field against the Sioux Indians, in South Dakota, and in the Battle of Wounded Knee he had a considerable taste of burnt powder, where the tribe that had massacred General Custer and his band was practically wiped out. The next year he was stationed at Fort Niobrara, in Nebraska, in command of the Sioux Indian Scouts.

This rapid summary of a busy and adventurous life on the plains does not convey any idea of its many activities. But it was an exceedingly valuable period of training to the young officer. He was finding himself, and learning something of the inner art of military science that he was later to put to such good use.

Here is the opinion of an officer who was Pershing's senior in the

Sixth Cavalry by six years—all of them spent in the Apache country:

"In those days, when a youngster joined a regiment, he was not expected to express himself on military matters until he had some little experience. But there was a certain something in Pershing's appearance and manner which made him an exception to the rule. Within a very short time after he came to the post, a senior officer would turn to him, and say: 'Pershing, what do you think of this?' and his opinion was such that we always listened to it. He was quiet, unobtrusive in his opinions, but when asked he always went to the meat of a question in a few words. From the first he had responsible duties thrown on him. We all learned to respect and like him. He was genial and full of fun. No matter what the work or what the play, he always took a willing and leading part. He worked hard and he played hard; but whenever he had work to do, he never let play interfere with it."

His experiences in the Wild West (and it was the Wild West in those days) cannot be passed over without relating one typical anecdote. Three cattle rustlers, white men, had gotten into a fight with the Zuni Indians, who caught them driving off some cattle. Three of the red men were killed before the outlaws were finally surrounded in a lonely cabin.

Word was sent of their predicament to the nearest fort, and Lieutenant Pershing was sent with a small detachment to their rescue. He rode straight up to the Zuni chief, who was now on the warpath, and told him he must call off his braves—that the United States Government would punish these men. The chief finally grunted assent, and Pershing strode forward alone into the clearing and approached the cabin. At any time a shot might have come out, but disregarding his own danger he went on, pushed open the door, and found himself looking into the muzzles of three guns.

A single false move on his part would probably have ended him, but he did not waver. He folded his arms and said quietly:

"Well, boys, I've come to get you."

The outlaws laughed noisily and swore by way of reply.

"You might as well come along," he went on, without raising his voice.

"My men are posted all around this cabin."

More profanity, but the men at last consented to go, if they could carry their guns. They wouldn't budge otherwise.

"You'll come as I say, and you'll be quick about it," said Pershing, a note of command coming into his voice.

And they did.

The next duty which fell to Lieutenant Pershing was quite different. From chasing Indians and outlaws on the plains, he was assigned to the task of putting some "half baked" cadets through their paces. In September, 1891, he became Professor of Military Science and Tactics at the University of Nebraska.

The discipline at this school was of a piece with that of other State colleges, where a certain amount of drilling was demanded, but beyond this the students were allowed to go their own gait. At Nebraska it had become pretty lax—but the arrival of the new instructor changed all that. A student of this time, in a recent article in The Red Cross Magazine, gives a humorous account of what happened.

It was the general belief that the students in these Western colleges, many of them farmers' sons, could never be taught the West Point idea. "But the Lieutenant who had just arrived from Lincoln received an impression startlingly in contrast to the general one. He looked over the big crowd of powerful young men, and, himself a storehouse and radiating center of energy and forcefulness, recognized the same qualities when he saw them.

"'By George! I've got the finest material in the world,'" he told the Chancellor, his steel-like eyes alight with enthusiasm. 'You could do anything with those boys. They've got the stuff in them! Watch me get it out!'

"And he proceeded to do so.

"By the middle of the first winter the battalion was in shape to drill together. Moreover, the boys had made a nickname for their leader, and nicknames mean a great deal in student life. He was universally called 'the Lieut.' (pronounced 'Loot,' of course, in the real American accent), as though there were but one lieutenant in the world. This he was called behind his back, of course. To his face they called him 'sir,' a title of respect which they had never thought to give to any man alive.

"By the end of that first academic year every man under him would have followed 'the Lieut.' straight into a prairie fire, and would have kept step while doing it."

As he gradually got his group of officers licked into shape, he found less to do personally. So he promptly complained to the Chancellor, to this effect, and asked, like Oliver Twist, for more.

"After a moment's stupefaction (the Lieut. was then doing five times the work that any officer before him had ever done) the Chancellor burst into a great laugh and suggested that the Lieut. should take the law course in the law school of the University. He added that if two men's work was not enough for him, he might do three men's, and teach some of the classes in the Department of Mathematics. Without changing his stride in the least, the young officer swept these two occupations along with him, bought some civilian clothes and a derby hat, and became both professor and student in the University, where he was also military attaché.

"During the next two years he ate up the law course with a fiery haste which raised the degree of class work to fever heat. Those who were fellow students with him, and survived, found the experience immensely stimulating."

Of course he graduated, and was thus entitled to write another title after his name—that of Bachelor of Arts. About this time, also, he was promoted to a first lieutenancy, the first official recognition for his many long months of work. Then he was sent back to the field again, to join the Tenth Cavalry at Fort Assiniboine, Montana.

Next came a welcome command to take the position of Assistant Instructor of Tactics, at West Point. It was almost like getting back home, to see these loved hills, the mighty river, and the familiar barracks again.

But after a few months here, the Spanish War broke out. Eager to get into the action, he resigned his position at the Military Academy, and was transferred to his former regiment, the Tenth Cavalry. This regiment was sent immediately to Santiago, and took part in the short but spirited fighting at El Caney and San Juan hill—where a certain Colonel of the Rough Riders was in evidence. Side by side these two crack regiments charged up the slope, dominated by the Spanish fort, and here Roosevelt and Pershing first met.

We would like to fancy these two intrepid soldiers as recognizing each other here in the din of battle. But the truth is sometimes more prosaic than fiction; and the truth compels us to reprint this little anecdote from The World's Work.

Five years after the Spanish War, when Roosevelt was President and

Pershing was a mere Captain, he was invited to luncheon at the White

House.

"Captain Pershing," said the President, when the party was seated at the table, "did I ever meet you in the Santiago campaign?"

"Yes, Mr. President, just once."

"When was that? What did I say?"

"Since there are ladies here, I can't repeat just what you said, Mr.

President."

There was a general laugh in which Roosevelt joined.

"Tell me the circumstances, then."

"Why, I had gone back with a mule team to Siboney, to get supplies for the men. The night was pitch black and it was raining torrents. The road was a streak of mud. On the way back to the front, I heard noise and confusion ahead. I knew it was a mired mule team. An officer in the uniform of a Rough Rider was trying to get the mules out of the mud, and his remarks, as I said a moment ago, should not be quoted before the ladies. I suggested that the best thing to do, was to take my mules and pull your wagon out, and then get your mules out. This was done, and we saluted and parted."

"Well," said Roosevelt, "if there ever was a time when a man would be justified in using bad language, it would be in the middle of a rainy night, with his mules down in the mud and his wagon loaded with things soldiers at the front needed."

Pershing, as a result of the Cuban campaign, was twice recommended for brevet commissions, for "personal bravery and untiring energy and faithfulness." General Baldwin said of him: "Pershing is the coolest man under fire I ever saw."

But it was not until 1901 that he became Captain. He had now been transferred at his own request to the Philippines. Whether or not he won promotion through the slow-moving machinery of the war office, his energetic spirit demanded action.

"The soldier's duty is to go wherever there is fighting," he said, and vigorously opposed the idea that he be given a swivel-chair job.

His first term of service in the Philippines was from 1899 to 1903. In the interval between his first and second assignments, the latter being as Governor of the Moros, he returned to America to serve on the General Staff, and also to act as special military observer in the Russo-Japanese War.

His duties during the years, while arduous and often filled with danger, were not of the sort to bring him to public notice. But they were being followed by the authorities at Washington, who have a way of ticketing every man in the service, as to his future value to the army. And Pershing was "making good." He had turned forty, before he was Captain. Out in the Philippines he worked up to a Major. Now advancement was to follow with a startling jump.

It all hinged upon that luncheon with Roosevelt, about which we have already told, and the fact that Roosevelt had a characteristic way of doing things. The step he now took was not a piece of favoritism toward Pershing—it arose from a desire to have the most efficient men at the head of the army.

Pershing was nominated for Brigadier General, and the nomination was confirmed. Of course it created a tremendous sensation in army circles. The President, by his action, had "jumped" the new General eight hundred and sixty-two orders.

On his return to the Philippines, as Governor of the Moro Province, he performed an invaluable service in bringing peace to this troubled district. He accomplished this, partly by force of arms, partly by persuasion. The little brown men found in this big Americano a man with whom they could not trifle, and also one on whose word they could rely.

It was not until 1914 that he was recalled from the Philippines, and then very shortly was sent across the Mexican border in the pursuit of Villa. It would seem as though this strong soldier was to have no rest—that his muscles were to be kept constantly inured to hardship—so that, in the event of a greater call to arms, here would be one commander trained to the minute.

The Fates had indeed been shaping Pershing from boyhood for a supreme task. Each step had been along the path to a definite goal.

The punitive expedition into Mexico was a case in point. It was a thankless job at best, and full of hardship and danger. A day's march of thirty miles across an alkali desert, under a blazing sun, is hardly a pleasure jaunt. And there were many such during those troubled months of 1916.

Then, one day, came a quiet message from Washington, asking General Pershing to report to the President. The results of that interview were momentous. The Great War in Europe was demanding the intervention of America. Our troops were to be sent across the seas to Europe for the first time in history. The Government needed a man upon whom it could absolutely rely to be Commander-in-chief of the Expeditionary Forces. Would General Pershing hold himself in readiness for this supreme task?

The veteran of thirty years of constant campaigning stiffened to attention. The eager look of battle—battle for the right—shone in his eye. Every line of his upstanding figure denoted confidence—a confidence that was to inspire all America, and then the world itself, in this choice of leader. He saluted.

"I will do my duty, sir," he said.

IMPORTANT DATES IN PERSHING'S LIFE

1860. September 13. John Joseph Pershing born. 1881. Entered Highland Military Academy, New York. 1882. Entered U. S. Military Academy, West Point. 1886. Graduated from West Point, senior cadet captain. Sent to southwest as second-lieutenant, 6th cavalry. 1891. Professor, military tactics, University of Nebraska. 1898. Took part in Spanish-American War. 1901. Captain, 1st Cavalry, Philippines. 1905. Married Frances Warren. 1906. Brigadier-general. 1914. Recalled from Philippines. 1915. Lost his wife and three children in a fire. 1915. Sent to Mexico in pursuit of Villa. 1917. Sent to France as commander-in-chief of American Expeditionary Force. 1919. Appointment of general made permanent. 1924. Retired from active service.

An interesting near contemporary account from:

BOYS' BOOK OF FAMOUS SOLDIERS

BY J. WALKER McSPADDEN

THE WORLD PUBLISHING CO.

CLEVELAND, OHIO —— NEW YORK, N. Y.

[Public Domain]

HAIG

THE MAN WHO LED "THE CONTEMPTIBLES"

"There goes young Haig. He says he intends to be a soldier."

The speaker was a young student at Oxford University, as he jerked his thumb in the direction of a slight but well-set-up fellow, a classmate, who went cantering past.

The chance remark, made more than once during the college days of Field Marshal Haig, struck the keynote of his career. From early boyhood Douglas Haig was going to be a soldier; and he stuck to his guns in a quiet, systematic way until he won out.

The story of Haig's life until the time of the Great War, was the opposite of spectacular, and even in it, his personal prowess was kept studiously in the background. With him it has always been: "My men did thus and so." Yet in his quiet way he has always made his presence felt with telling effect. He has been the man behind the man behind the gun.

By birth Haig was a "Fifer," which sounds military without being so. He was a native of Cameronbridge, County of Fife, and came of the strictest Presbyterian Scotch. If he had lived a few centuries back he would have been a Covenanter—the kind that carried a Bible in one hand and a gun in the other. He was born, June 19, 1861, the youngest son of John Haig, a local Justice of the Peace. His mother was a Veitch of Midlothian.

The family, while not wealthy, was comfortably situated. The Haig children grew up as countrywise rather than townbred, having many a romp over the rolling country leading to the Highlands. But more than once on such a jaunt would come the inquiry: "Where's Douglas?" (We doubt whether they ever shortened it to "Doug," as they would have done in America.) And back would come the answer: "Oh, he stayed by the house, the morn. He got a new book frae the library, ye ken."

Douglas was, indeed, bookish and was inclined to favor the inglenook rather than the heather. As he grew older he discovered a strong liking for books on theology. It was the old Presbyterian streak cropping out.

The last thing one would expect from such a boy, was to become a soldier. A divinity student, yes,—perhaps a college professor—but a soldier, never! Yet it was to soldiering that this quiet boy turned.

The one thing which linked him up with the field was horsemanship. He was always a devotee of riding, and soon learned to ride well, with a natural ease and grace.

He received a general education at Clifton, then entered Brasenose College, Oxford, at the age of twenty. He was never a "hail-fellow-well-met" sort of person. Reserve was his hallmark. But the longer he stayed in college, the more of an outdoorsman he became. Every afternoon would find him mounted on his big gray horse for a gallop across the moors, or perhaps an exciting canter behind the hounds on the scent of a fox. It was then that his habitual reserve would melt away, and he would wave his hat and cheer like a high-school boy.

The record of his classes is in no sense remarkable. He turned in neat and precise papers, without making shining marks in any particular study. Literature and science were his best subjects.

"Well, son, how goes it now?" his father would ask. "Ready to make a lawyer out of yourself?"

Douglas would shake his head. He could never share his father's enthusiasm for the law. "I guess not, father," he would reply quietly. "Somehow, I am not built that way. I want a try at soldier life."

So his father let him follow his bent, and procured for him a position in the Seventh Regiment of Hussars. His career as a soldier was threatened at the outset by the refusal of the medical board to admit him to the Staff College on the ground that he was color-blind; but this decision was over-ruled by the Duke of Cambridge, then commander-in-chief, who nominated him personally. This was in 1885. England was then as nearly at peace as she ever became, and it seemed that young Haig was destined to become a feather-bed soldier.

But it was not for long. They presently began to stir up trouble down in Egypt, and England found, as on many previous occasions, that she didn't have half enough regulars for the job in hand. The revolt of the Mahdi had occurred, Khartoum had fallen, and the brave Gordon had lost his life.

A relief expedition into the Soudan was organized under the command of a tall, stern soldier named Kitchener, who began his first preparations to march into the interior about the time that Haig was putting on his first Hussar uniform.

The campaign in Egypt dragged, despite the zeal of the leader. In disgust, Kitchener returned to England to demand more men. The request was at last granted, and by December, 1888, he was in command of a force of over 4,000 troops, of which number 750 were British regulars! Those were indeed the days of the "Little Contemptibles," but right manfully they measured up to their tasks. And in the British force was the Seventh Hussars, including Haig. He was about to achieve his life's ambition, at last—to see real service as a British soldier.

Haig was then a well-knit young man of twenty-seven. His outdoor exercise had browned and hardened him, until he looked thoroughly fit for the exacting job ahead. He was slightly under medium size, but tough and wiry to the last degree. His shoulders were broad, his head well set, and the bulging calves of his legs showed the born cavalryman. He had fair, almost sandy hair, a close-cropped mustache, and steel-blue eyes which met honestly and unflinchingly the gaze of any with whom he talked. He looked then, as in later years, "every inch a soldier," and speedily won the confidence of his superiors.

The silent Kitchener, who was a keen judge of men, soon took a fancy to this quiet young lieutenant. A friendship sprang up between them, that was destined to bear far-reaching fruit. The two men were both reserved in demeanor, but in a different sort of way. Kitchener was taciturn and often inclined to growl. Haig was a man of few words and no intimates, but greeted all with a pleasant smile. To this young Scotsman Kitchener unbent more than was his wont, and was actually seen shaking hands with him, at parting, on a later occasion; which all goes to show that even commanding officers can be human.

On the march into the Soudan, Kitchener was in command of the Egyptian Cavalry also. The Khedive was exceedingly anxious that the rebellion be crushed speedily, and had made Kitchener the "sirdar." One of the first actions in this campaign was the Battle of Gemaizeh. Three brigades were sent to storm the forts held by the dervishes, and a heavy and sustained fire from three sides soon drove the enemy out in disorder. Some 500 dervishes were slain, and the remainder numbering several thousand fled across the desert toward Handub—closely pursued by the British Hussars and the Egyptian cavalry.

This was only the first of many such actions. Further and further south the rebels were driven. Kitchener pushed a light railroad across the desert as he advanced, so that he would not suffer from the same mistake which had ended Gordon—getting cut off from his base of supplies.

And in the thick of it was Haig—learning the actual trade of war in these frequent brushes on the desert—riding hard by day, sleeping the sleep of exhaustion at night. On more than one occasion the Chief sent him on a special quest with important messages, and always Haig got through. He seemed to bear a charmed life. "Lucky Haig," the men began to call him, and the title stuck.

Entering the desert as a Lieutenant, he was promoted to Captain, then brevetted a Major. He was mentioned in the despatches for bravery, and won a medal from the Khedive.

All this was not done in a few short months. The Egyptian campaign stretched into years, and at times must have seemed fearfully monotonous to these soldiers so far removed from home comforts. Here is the way one writer describes the Soudan:

"The scenery, it must be owned, was monotonous, and yet not without haunting beauty. Mile on mile, hour on hour, we glided through sheer desert. Yellow sand to right and left—now stretching away endlessly, now a valley between small broken hills. Sometimes the hills sloped away from us, then they closed in again. Now they were diaphanous blue on the horizon, now soft purple as we ran under their flanks. But always they were steeped through and through with sun—hazy, immobile, silent."

One of the culminating battles of the campaign was that of Atbara, where the backbone of the dervish rebellion was broken. It is estimated that here 8,000 dervishes were killed, 2,000 wounded, and 2,000 made prisoners. The battle began with a bombardment by the field guns. Then came the British cavalry at a gallop—the Camerons in front, and columns of Warwicks, Seaforths, and Lincolns behind. Bugles, bagpipes, and the instruments of the native regiments made strange music as the army pressed forward intent on reaching the river bank.

The native stockades were reinforced with thorn bushes, but these were torn away by the men, with their bare hands, in their eagerness to advance. Haig's regiment was one of the first to penetrate, but once past the stockade they encountered many of the defenders who put up a fierce fight. Several British officers lost their lives, and it was due to Haig's agility and presence of mind that he was not at the least severely wounded. Two dervishes attacked him at once from opposite sides. One aimed a slashing blow at his head with a scimitar. Haig quickly ducked and the scimitar went crashing against the weapon of the other dervish. Haig's luck again!

Others were not so fortunate. "Never mind me, lads, go on," said Major Urquhart with his dying breath. "Go on, my company, and give it to them," gasped Captain Findlay as he fell. At the head of the attacking party strode Piper Stewart, playing "The March of the Cameron Men," until five bullets laid him low. Truly the spirit of the fiery old Covenanters was there!

The final battle of the Soudanese campaign, Khartoum, put the finishing touches to the rebellion, and gave to Kitchener the title "K. of K."—Kitchener of Khartoum. This battle was noteworthy in employing the cavalry in an open charge across the plains against the dervish infantry. It was just such a charge as a skilled horseman such as Haig would keenly enjoy, despite the danger. Winston Churchill, the British Minister, thus describes it:

"The heads of the squadrons wheeled slowly to the left, and the Lancers, breaking into a trot, began to cross the dervish front in column of troops. Thereupon and with one accord the blue-clad men dropped on their knees, and there burst out a loud, crackling fire of musketry. It was hardly possible to miss such a target at such a range. Horses and men fell at once. The only course was plain and welcome to all. The Colonel, nearer than his regiment, already saw what lay behind the skirmishers. He ordered 'Right wheel into line' to be sounded. The trumpet jerked out a shrill note, heard faintly above the trampling of the horses and the noise of the rifles. On the instant the troops swung round and locked up into a long, galloping line.

"Two hundred and fifty yards away, the dark blue men were firing madly in a thin film of light-blue smoke. Their bullets struck the hard gravel into the air, and the troopers, to shield their faces from the stinging dust, bowed their helmets forward, like the Cuirassiers at Waterloo. The pace was fast and the distance short. Yet before it was half covered the whole aspect of the affair changed. A deep crease in the ground—a dry watercourse, a khor—appeared where all had seemed smooth, level plain; and from it there sprang, with the suddenness of a pantomime effect and a high-pitched yell, a dense white mass of men nearly as long as our front and about twelve deep. A score of horsemen and a dozen bright flags rose as if by magic from the earth. The Lancers acknowledged the apparition only by an increase of pace."

In such a mêlée as then followed, that trooper was lucky indeed who escaped without a scratch.

As a result of his bravery at Atbara and Khartoum, Haig's name was mentioned in the official despatches. He returned to England wearing the Khedive's medal and the honorary title of Major.

It is probable, however, that little more would have been heard of him, had not the South African War broken out, soon after. It is the lot of military men to vegetate in days of peace. They live upon action. Haig was no exception to this rule. He welcomed new fields. He went to South Africa as aide and right-hand man to Sir John French—the general whom he was to succeed in later years on the battlefields of France.

In this war, Haig is not credited with many personal exploits. His was essentially a thinking part. Yet he served as chief of staff in a series of minor but important operations about Colesburg, which prepared the way for Roberts's advance. As usual Haig pinned his faith upon the cavalry. All his life he had made a close study of this arm of the service, and was of opinion that it was not utilized in modern warfare nearly so much as it should be. He was a warm admirer of the American officer, J. E. B. Stuart, the Confederate General whose dashing tactics turned the scale in so many encounters.

Now he tried the same strategy in the operations around Colesburg—and paved the way for later victory.

Haig somewhat resembled another Southern leader, Stonewall Jackson, in his piety. It was not ostentatious, but simply part and parcel of the man, due to his Presbyterian training. Haig did not swear or gamble or dance all night. He was more apt to be found in his tent, when off duty, either reading or writing.

They tell of him that, one day at the officers' mess, after a particularly lively brush with the Boers, the quartermaster asked him if he had lost anything.

"Yes," replied Haig solemnly, "my Bible!"

Not once did his countenance relax its gravity, as he met the grinning faces across the table.

But despite their chaffing, there was not a man there who did not respect the courage of his convictions, no less than the bravery of the man himself. Almost daily he risked his life in these cavalry operations—until the "Haig luck" became a watchword.

The end of the South African War found Haig promoted to acting Adjutant

General of the Cavalry, and soon after his return home he was made

Lieutenant Colonel, in command of the Seventeenth Lancers. This was in

1901.

About this time he paid a visit to Germany, then at peace and professing a warm affection for England. One result of this visit was a letter which showed him possessed with wonderful powers of analysis and foresight. He practically predicted the war that was to come. He summed up his observations in a long letter to a friend which, in the light of events of the War, is little short of uncanny. It gave the German plan with a mastery of detail, shrewd prophecy, and earnest warning. The future commander-in-chief of the British armies in France was convinced of the certainty of the conflict and besought the authorities to make better preparation—but his warnings fell upon deaf ears.

It required thirteen years to demonstrate the truth of Haig's predictions, and then the blow fell. The Kaiser viewed his strong hosts and boasted that he would soon wipe out England's "contemptible little army." He very nearly did so, and would certainly have succeeded, had it not been for the fighting spirit of such men as Haig.

During the intervening years since the South African campaign he had risen by fairly rapid stages to Inspector-General of the Cavalry in India—a situation which he handled with great skill for three years—then Major General, and Lieutenant General.

At the outbreak of the World War, he was hurriedly sent to France, under the command of Sir John French, his old leader in Africa. French was generosity itself in his praise of Haig in these early days of disaster.

In the retreat from Mons it was "the skilful manner in which Sir Douglas Haig extricated his corps from an exceptionally difficult position in the darkness of the night," that won his laudation. At the Aisne, on September 14, 1914, "the action of the First Corps on this day, under the direction and command of Sir Douglas Haig, was of so skilful, bold, and decisive a character, that he gained positions which alone have enabled me to maintain my position for more than three weeks of very severe fighting on the north bank of the river."

In the first battle of Ypres, the chief honors of victory were again awarded to him:

"Throughout this trying period, Sir Douglas Haig, aided by his divisional commanders and his brigade commanders, held the line with marvelous tenacity and undaunted courage."

Again and again, the generous French pays tribute to his friend, which while deserved reflects no less honor upon the speaker. He was big enough to share honor.

It is not strange, therefore, when French was superseded, for strategic reasons, that Haig should have been given the chief command. The appointment, however, left most of the world frankly amazed. Haig had come forward so quietly that few save those in official circles knew anything about him. It was nevertheless but a matter of weeks, possibly days, before a quiet confidence born of the man himself was manifest everywhere.

One war correspondent who visited headquarters in the midst of the

War's turmoil, thus describes his visit:

"The environment of the Commander-in-chief is strongly suggestive of his conduct of the war. Before war became a thing of precise science, the headquarters of an army head seethed with all the picturesque details so common to pictures of martial life. Couriers mounted on foam-flecked horses dashed to and fro. The air was vibrant with action; the fate of battle showed on the face of the humblest orderly. But today 'G. H. Q.'—as headquarters are familiarly known—are totally different. Although army units have risen from thousands to millions of men, and fields of operations stretch from sea to sea, and more ammunition is expended in a single engagement than was employed in entire wars of other days, absolute serenity prevails. It is only when your imagination conjures up the picture of flame and fury that lies beyond the horizon line that you get a thrill.

"An occasional motorcar driven by a soldier-chauffeur chugs up the gravel road to the chateau and from it emerge earnest-faced officers whose visits are usually brief. Neither time nor words are wasted when myriad lives hang in the balance and an empire is at stake. Inside and out there is an atmosphere of quiet confidence, born of unobtrusive efficiency."

The same writer on meeting Haig says: "I found myself in a presence that, even without the slightest clue to its profession, would have unconsciously impressed itself as military. Dignity, distinction, and a gracious reserve mingle in his bearing. I have rarely seen a masculine face so handsome and yet so strong. His hair and mustache are fair, and his clear, almost steely-blue eyes search you, but not unkindly. His chest is broad and deep, yet scarcely broad enough for the rows of service and order ribbons that plant a mass of color against the background of khaki. . . .

"Into every detail of daily life at General Headquarters the Commander's character is impressed. After lunch, for example, he spends an hour alone, and in this period of meditation the whole fateful panorama of the war passes before him. When it is over the wires splutter and the fierce life of the coming night—the Army does not begin to fight until most people go to sleep—is ordained.

"This finished, the brief period of respite begins. Rain or shine, his favorite horse is brought up to the door, and he goes for a ride, usually accompanied by one or two young staff-officers. I have seen Sir Douglas Haig galloping along those smooth French roads, head up, eyes ahead—a memorable figure of grace and motion. He rides like those latter-day centaurs—the Australian ranger and the American cowboy. He seems part of his horse."

Such was the man who did his full share in turning the German tide. Throughout the four long years of war, he faced the enemy with a calm courage which if it ever wavered gave no outward sign. And that is one reason why the Little Contemptibles grew and grew until they became a mighty barrier stretching across the pathway of the invader from sea to sea, and saying with their Allies:

"You shall not pass!"

IMPORTANT DATES IN HAIG'S LIFE

1861. June 19. Douglas Haig born. 1880. Entered Brasenose College, Oxford. 1885. Joined 7th Hussars, British army. 1898. Served in Soudan, mentioned in despatches, and brevetted major. 1899. Served in South Africa. D. A. A. G. for cavalry; then staff officer to General French. 1901. Lieutenant-colonel commanding 17th Lancers. 1903. Inspector-general, cavalry, India. 1904. Major-general. 1910. Lieutenant-general. 1914. General, commanding First Army in France. 1915. Commander-in-chief of British forces. 1917. Field marshal. 1919. Created an earl. 1928. January 30. Died in England.

PERSHING

THE LEADER OF AMERICA'S BIGGEST ARMY

It was a historic moment, on that June day, in the third year of the World War. On the landing stage at the French harbor of Boulogne was drawn up a company of French soldiers, who looked eagerly at the approaching steamer. They were not dress parade soldiers nor smart cadets—only battle-scarred veterans home from the trenches, with the tired look of war in their eyes. For three years they had been hoping and praying that the Americans would come—and here they were at last!

As the steamer slowly approached the dock, a small group of officers might be discerned, looking as eagerly landward as the men on shore had sought them out. In the center of this group stood a man in the uniform of a General in the United States Army. There was, however, little to distinguish his dress from that of his staff, except the marks of rank on his collar, and the service ribbons across his breast. To those who could read the insignia, they spelled many days of arduous duty in places far removed. America was sending a seasoned soldier, one tried out as by fire.

The man's face was seamed from exposure to the suns of the tropics and the sands of the desert. But his dark eyes glowed with the untamable fire of youth. He was full six feet in height, straight, broad-shouldered, and muscular. The well-formed legs betrayed the old-time calvalryman. The alert poise of the man showed a nature constantly on guard against surprise—the typical soldier in action.

Such was General Pershing when he set foot on foreign shore at the head of an American army—the first time in history that our soldiers had ever served on European soil. America was at last repaying to France her debt of gratitude, for aid received nearly a century and a half earlier. And it was an Alsatian by descent who could now say:

"Lafayette, we come!"

Who was this man who had been selected for so important a task? The eyes of the whole world were upon him, when he reached France. His was a task of tremendous difficulties, and a single slip on his part would have brought shame upon his country, no less than upon himself. That he was to succeed, and to win the official thanks of Congress are now matters of history. The story of his wonderful campaign against the best that Germany could send against him is also an oft-told story. But the rise of the man himself to such commanding position is a tale not so familiar, yet none the less interesting.

The great-grandfather of General Pershing was an emigrant from Alsace—fleeing as a boy from the military service of the Teutons. He worked his way across to Baltimore, and not long thereafter volunteered to fight in the American Revolution. His was the spirit of freedom. He fled to escape a service that was hateful, because it represented tyranny; but was glad to serve in the cause of liberty.

The original family name was Pfirsching, but was soon shortened to its present form. The Pershings got land grants in Pennsylvania, and began to prosper. As the clan multiplied the sons and grandsons began to scatter. They had the pioneer spirit of their ancestors.

At length, John F. Pershing, a grandson of Daniel, the first immigrant, went to the Middle West, to work on building railroads. These were the days, just before the Civil War, when railroads were being thrown forward everywhere. Young Pershing had early caught the fever, and had worked with construction gangs in Kentucky and Tennessee. Now as the railroads pushed still further West, he went with them as section foreman—after first persuading an attractive Nashville girl, Ann Thompson, to go with him as his wife.

Their honeymoon was spent among the hardships of a construction camp in

Missouri; and here at Laclede, in a very primitive house, John Joseph

Pershing was born, September 13, 1860.

The boy inherited a sturdy frame and a love of freedom from both sides of the family. His mother had come of a race quite as good as that of his father. They were honest, law-abiding, God-fearing people, who saw to it that John and the other eight children who followed were reared soberly and strictly. The Bible lay on the center table and the willow switch hung conveniently behind the door.

After the line of railroad was completed upon which the father had worked, he came to Laclede and invested his savings in a small general store. It proved a profitable venture. It was the only one in town, and Pershing's reputation for square-dealing brought him many customers. A neighbor pays him this tribute:

"John F. Pershing was a man of commanding presence. He was a great family man and loved his family devotedly. He was not lax, and ruled his family well.